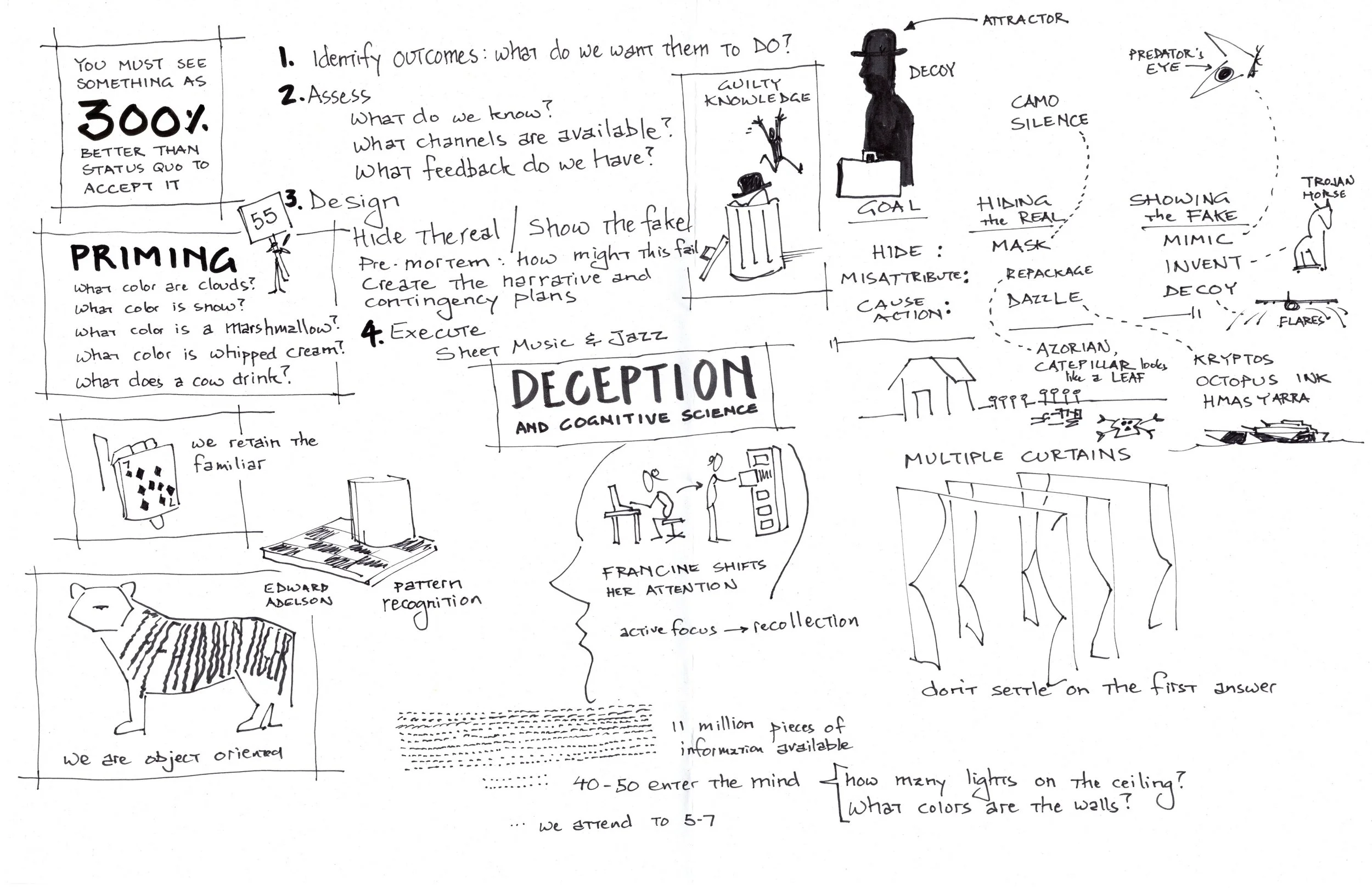

How to Design for Attention, Illusion, and Belief

Content by Ludus Lab.

Sketchnotes by Lizard Brain.

What if getting someone to change their mind wasn’t about logic, but illusion?

In one of our favorite sketchnotes, we study how deception and cognitive science intersect to shape human attention, perception, and decision-making. These principles aren’t just for stage magicians or spy agencies—they’re for anyone trying to help humans navigate complex ideas, spot patterns, and choose wisely.

The 300% Rule

To accept a change, people need to see it as 300% better than the status quo. Why? Because humans are loss-averse. Change means risk. To override our natural preference for the familiar, the new must feel dramatically more compelling.

That’s your bar.

Step-by-Step: Designing Deception (For Good)

Identify Outcomes

What do we want them to do?Assess the Landscape

What do we already know?

What channels can we use?

What feedback loops are in place?Design the Illusion

Hide the real / Show the fake

Run a premortem: How might this fail?

Build in narratives and backup plans.

Execute

Like jazz. You’ve got sheet music, but you’ll need to improvise.

Priming, Patterns, and Perception

Ask someone:

What color are clouds?

What color is snow?

What does a cow drink?

Most will answer “milk.” That’s priming—a cognitive shortcut where previous exposure shapes how we interpret new information.

We’re also wired for pattern recognition. We cling to the familiar. We simplify complexity by matching it to what we already know. Edward Adelson’s visual illusions (like the checker shadow) show how easily our brains can be misled by context.

We see what we expect to see.

Attention Is Scarce. Use It Wisely.

Each second, we’re bombarded with 11 million bits of sensory data. Only 40 to 50 bits make it through to conscious awareness.

We can actively focus on 5 to 7 things at once—tops.

This means:

You can redirect attention with ease.

You can overwhelm someone into missing the obvious.

You can hide a message in plain sight.

That’s why deception works. Not because we’re dumb, but because we’re efficient.

The Mechanics of Misdirection

Here’s how deception works in practice:

Hide the real: Mask, repackage, camouflage.

Show the fake: Mimic, invent, dazzle.

Use decoys and attractors to pull focus away from your real move.

Always have multiple curtains—so people don’t settle on the first answer.

Examples from history:

The Trojan Horse: Deception as a gift.

Project Azorian: A sunken Soviet submarine retrieved by the CIA under the cover of a mining operation.

Kryptos: A still-unsolved encrypted sculpture sitting in front of CIA HQ.

Octopus ink, caterpillars that look like leaves, WWI dazzle camouflage—nature and warfare both know how to manipulate what the eye sees.

Memory, Focus, and the Story We Tell

Change your focus, and you change your memory. That’s not metaphor—it’s neuroscience.

In the sketchnote, “Francine shifts her attention,” and suddenly her recollection changes. The story she tells herself shifts. As facilitators, designers, and educators, we’re often shaping stories—about what’s real, what matters, and what to do next.

So ask:

How many lights are on the ceiling?

What color are the walls?

Chances are, you didn’t notice. But now that your attention is there—you can’t unsee it.

Use This for Good

This isn’t about manipulation. It’s about clarity. Humans operate with limited attention, driven by pattern, primed by context. Knowing how to ethically guide that attention is part of being a responsible leader, communicator, and thinker.

So yes—deception has its place.

Just make sure you’re using it to help people see what’s true.

Want to go deeper?

Let’s run a session on how to design with cognitive science in mind. We'll bring the post-its, illusions, and mind-expanding questions. Contact Lizard Brain today.