When Options Aren’t Equal

Image created by Brian Tarallo

How groups can make good decisions when alternatives have different costs

“OK, kids. Where should we go on vacation this year?”

Having four kids, each with their own unique personality, preference, and temperaments makes dinner conversation the perfect test bed for facilitation modalities. It’s also an opportunity to find problems in those modalities.

So at dinner, if I give them these options for vacations:

Universal Studios

Beach Airbnb

Shenandoah Cabin

Appalachian Trail Hiking & Camping

3 City Road Trip

Boston to Visit Family

Arizona to Visit Family

…there are two big categories of ways I can set this up as a group decision making process.

(Quick caveat: I COULD just decide for them. That’s the equivalent of “leader decides,” which is a perfectly valid way of making a decision. It’s the fastest, and also has the lowest buy-in: which in our family translates to grumbling, grumpy kids.)

Anyway, back to those two big categories.

Preference-based decision making. This is voting in all its varieties: straw polls, gladiator polls, fist of five, dot voting, 1-N lists, and gradients of agreement, just to name a few. Preference-based decision making internalizes all the factors and criteria into the heads of the people deciding. As a leader, you have to trust that the people making the decision are taking into account all the costs and complexities of each option, and are weighing those costs against their own perspectives on the potential returns. Market-driven organizations and teams that care more about “doing things fast” or “doing things first” tend to rely on preference-based decision making.

Preference-based decision making is fast and relies on mutual trust and shared accountability being more important than individual agendas.

Criteria-based decision making. This is where the group breaks down each option into its component parts and assigns a weight against predetermined criteria: 2x2 grids, importance/impact matrices, force field diagrams, and decision models, just to name a few. Criteria-based decision making externalizes factors and criteria into repeatable processes not dependent on who’s in the room. Bureaucracies and organizations that care more about “doing things right” tend to rely on criteria-based decision making. Criteria-based decision making is a slow grind, and may still result in low buy-in. A decision-making process that completely divorces itself from individual preference feels more like filling out tax forms than choosing which of the 31 flavors of ice cream you want.

Criteria-based decision making is slow and doesn’t depend on trust or shared accountability.

But what happens when the options aren’t equal?

Back to the vacation: let’s say I want to do some form of preference-based voting, because I want the kids’ buy-in, translating less grumbling and grumpiness.

In this scenario, if I were to do a straw poll, dot vote, the most likely outcome would probably be Universal Studios: it’s the most relative fun for all of them.

But hang on a second: I’m paying for this. Universal Studios would be the most expensive option. It might be the best for the kids, but it’s the costliest for me. The kids might not care about cost, but I do. So I have to come up with a way of internalizing that cost, so it becomes part of their preference-based criteria.

In this case, one way to do that is time. When I add the dimension of time, now the list looks like this:

3 days at Universal Studios

5 days at Beach Airbnb

5 days at a Shenandoah Cabin

5 days of Appalachian Trail Hiking & Camping

7 days for a 3 City Road Trip

7 days Boston to Visit Family

7 days Arizona to Visit Family

All of a sudden, the kids might consider a longer trip to Arizona rather than a shorter trip to Universal.

But what if you can choose more than one option?

Let’s complicate this even further. Let’s say you’re not limited to one option: which, in reality, is rarely the case. We need to internalize another factor, which in this case might as well be the thing that I was worried about from the beginning: cost.

Now my list looks like this:

3 days at Universal Studios - $10000

5 days at Beach Airbnb - $5000

5 days at a Shenandoah Cabin - $5000

5 days of AT Hiking & Camping - $1500

7 days for a 3 City Road Trip - $3000

7 days Boston to Visit Family - $3000

7 days Arizona to Visit Family - $5000

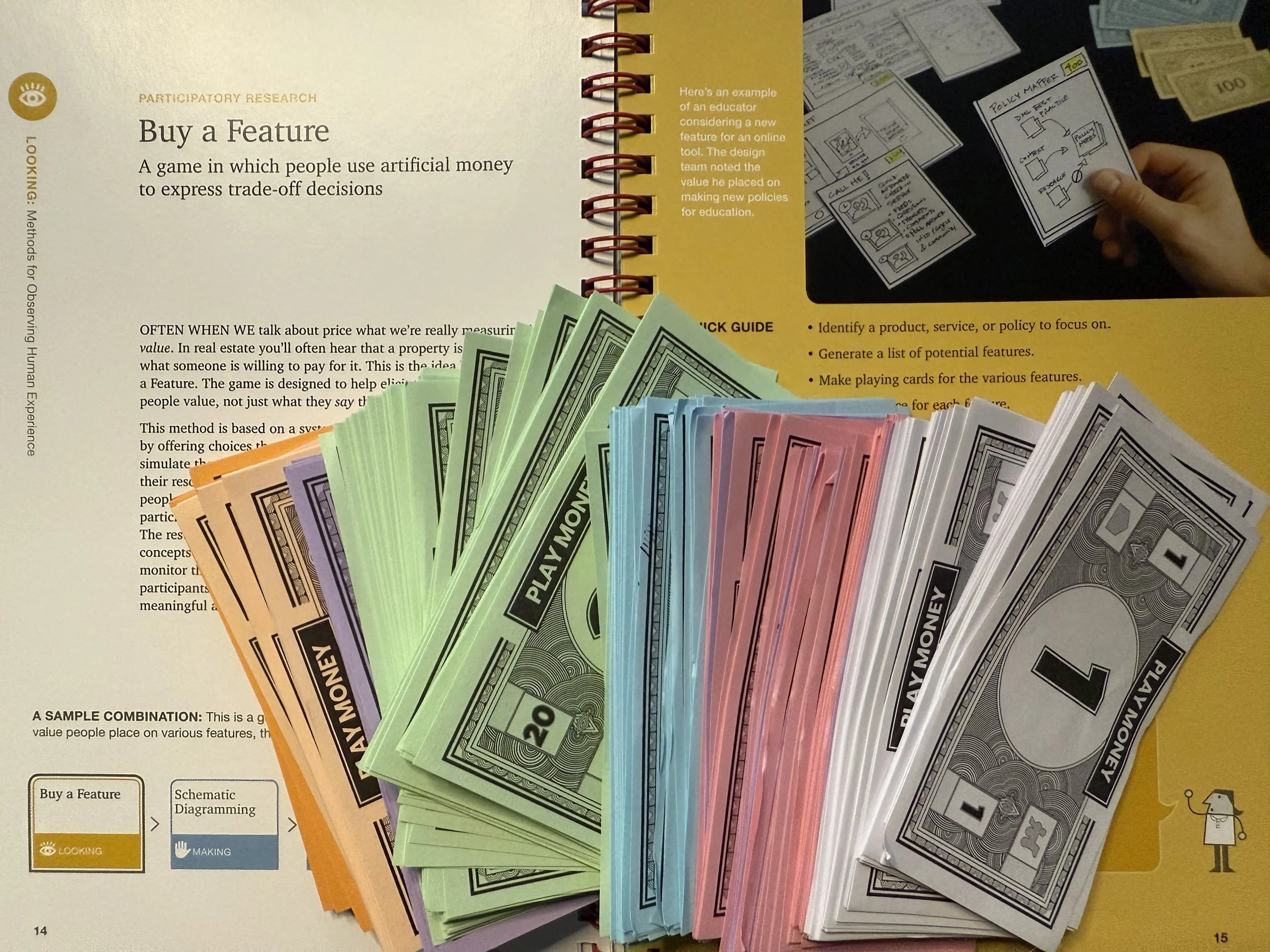

We’ve just recreated buy-a-feature.

“OK kids! Here’s our options for vacations this year. I’m passing you each $10,000 of Monopoly money. You can distribute it however you want. You could get one 3-day trip to Universal Studios. Or you could opt for 5 days at the beach AND 5 days at a cabin. Or hiking, a road trip, and Boston! It’s up to you.”

What I like about buy-a-feature is that…

It has HUGE buy-in. No grumpiness. No grumbling. And no one feeling like their voice was cut out of the conversation.

It distributes the leader’s concerns across the group, which is great for developing future leaders.

It’s just as fast as any preference-based decision making method.

It retains some of the nuance of criteria-based decision making.

It’s fun. Seriously fun. Everyone, adults included, adults especially, loves playing with Monopoly money.

It DOES take time on the front end to come up with the relative “costs” of each option and resulting menu participants use to guide their decision making. But I find that buy-a-feature works especially well for outside groups to judge options that they may not have nuanced around.

For example, last week I facilitated a focus group as they decided which website features were most important to them. A traditional vote wouldn’t have accounted for the level of effort each feature would have taken. So we used buy-a-feature: “If you want the AI chatbot, that’s $5. But if you want calendar integration, that’s $2.”

How to facilitate buy-a-feature

Before the meeting:

List the alternatives.

With whoever has the best sense of cost or level of effort, come up with relative costs for each alternative. It doesn’t matter if costs are close to reality (like the vacation) or artificially low to account for Monopoly money denominations (like the website features.) What matters is that the costs are loosely proportional to each other.

Decide how much “money” you’re going to allocate to the participants. That may translate to budget, capacity, a period of time, or however else you manage the volume of work.

I like to draw up quick, single-image posters, one alternative per poster, on flipcharts and post them around the room. Include the alternative name and cost on the poster.

Tape an envelope to the poster.

Optionally, create a “sushi menu” handout summarizing features and costs for participants to refer to.

During the meeting:

Pass out stacks of Monopoly money in low denominations. It’s rare that people will pick the one big option (like Universal Studios.) Most folks want to spread the wealth.

Explain that people can spend their money however they want to, but they HAVE to spend the correct amount (no slipping $2 into a $5 poster), they may not further divide their money (by cutting it in half) or selling it to each other for real money (I have seen both of these dynamics happen.)

Allow time for participants to think about how they want to allocate their money, do a gallery walk, and buy their features, slipping cash into the envelopes. They can mark up their sushi menus as references during later discussions.

Once all the money has been distributed, total up the cash spent on each feature. Then divide that amount by the cost of each feature to come up with your votes. For example:

3 days at Universal Studios - $10000.

Cash in envelope: $30000 / 10000 = 3 votes

5 days at Beach Airbnb - $5000

Cash in envelope: $20000 / 50000 = 4 votes

5 days at a Shenandoah Cabin - $5000

Cash in envelope: $25000 / 5000 = 5 votes

5 days of AT Hiking & Camping - $1500

Cash in envelope: $0 / 10000 = 0 votes

7 days for a 3 City Road Trip - $3000

Cash in envelope: $9000 / 3000 = 3 votes

7 days Boston to Visit Family - $3000

Cash in envelope: $6000 / 3000 = 2 votes

7 days Arizona to Visit Family - $5000

Cash in envelope: $15000 / 5000 = 3 votes

So in this case, the Shendoah Cabin is the winner with 5 votes, followed by Beach Airbnb. And since our total budget is $10000, we can do both: 10 days of beach and cabin vacation vs. 3 days of Universal. And no grumpiness, no grumbling.

Epilogue: I was a little bummed that nobody picked the Appalachian Trail. So my wife and I left the kids at home and did it ourselves, for about $250 for new gear and a celebratory breakfast. And we all lived happily ever after.